Media

Media

This section brings together critical texts, interviews, video materials, and press documents related to my artistic practice.

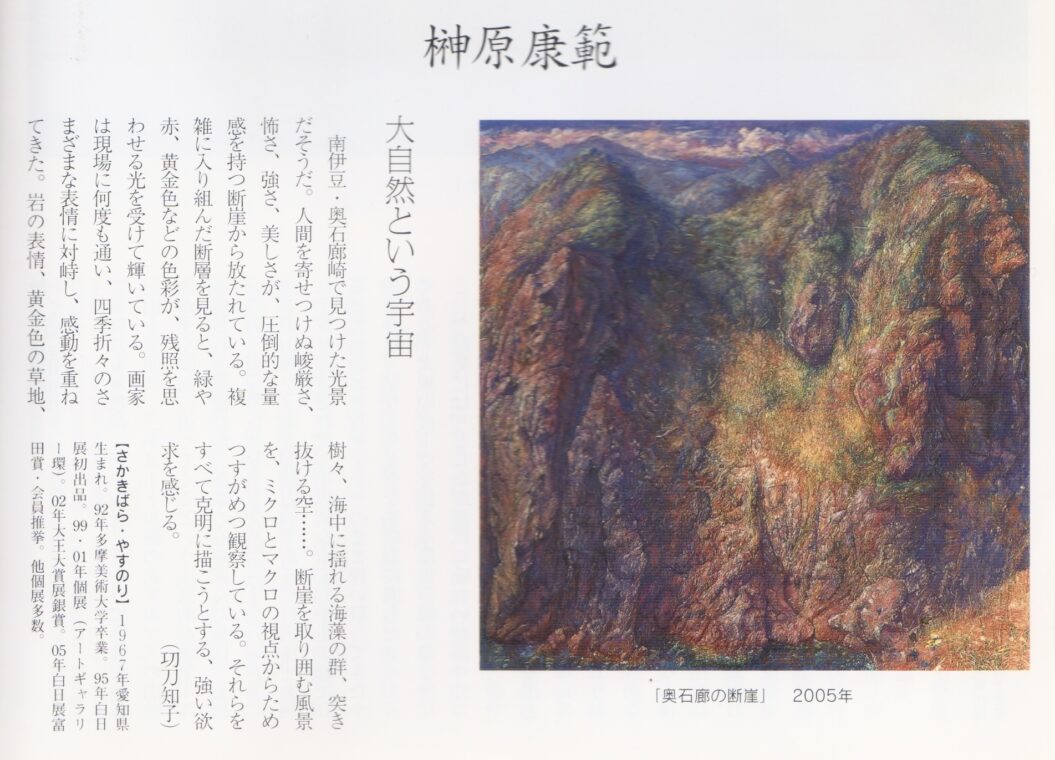

Rather than presenting my own voice, these materials reflect how my work has been observed, interpreted, and discussed by others across different cultural and geographical contexts, including Japan, South and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific region.

Through essays, conversations, and visual records, this archive offers multiple perspectives on my work and its ongoing dialogue with place, memory, and human experience.

⸻

🔹 Critical Texts

Essays and critical writings by poets, critics, and writers who have engaged deeply with my work and its philosophical and cultural background.

⸻

🔹 Interviews

Conversations with journalists and writers, focusing on my artistic process, fieldwork, and experiences in different cities and regions.

⸻

🔹 Video

Video materials including interviews, documentaries, and field recordings that document both my work and the environments in which it was created.

⸻

🔹 Press

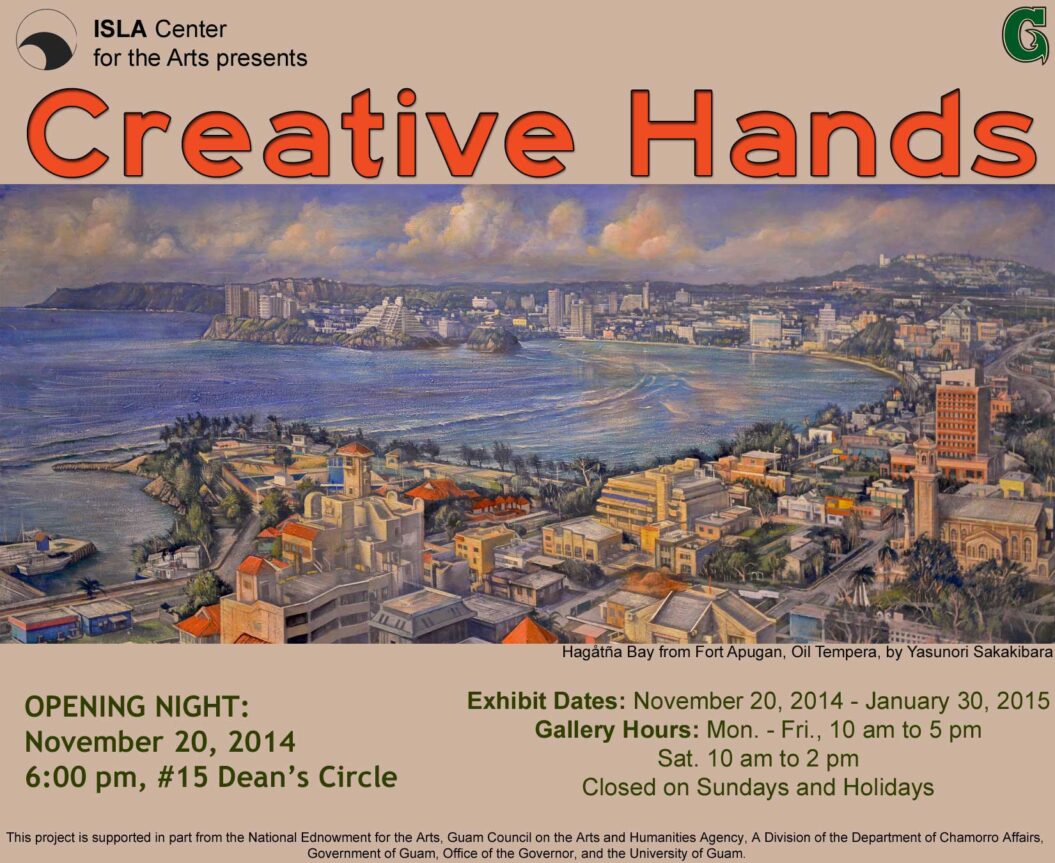

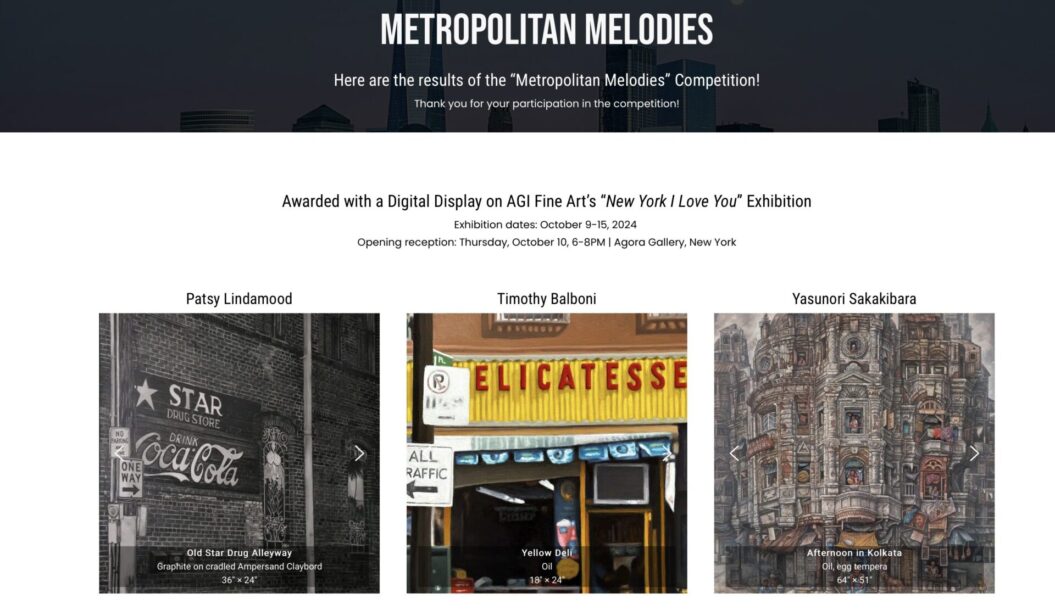

Exhibition posters, newspaper articles, and published materials documenting exhibitions and public presentations of my work.

THE SUNDAY POST SUNDAY, JUNE 5, 2016

Traditions remembered,disputed

Contemporary meets traditional painting, carving, dance and film at museum

Story & photos by Amanda Pampuro

“The Festival of Pacific Arts has come and gone, but the Guam Museum, a concrete wonder of sling stone and steel, will stand for many years to come. Nestled strategically

between Chamorro Village and Dulce Nombre

de Maria Cathedral-Basilica, the building bridges

the shoreline and innards of the capital city, and

gives a great excuse to park far and walk.

In its first week of life, the museum has hosted

dozen of films and dances from local and visit-

ing festival delegates. Inside, three exhibition

halls packed in paintings, carvings, weav-

ings, sculptures, videos, and photos reflecting

commonalities – the beauty of our beaches and

our fear of being forgotten – and our distinct

differences for the tide that forms tradition.

beats a little differently against each shore.

From the Solomon Islands Nelson Horipua

brought to Guam a dozen paintings depict-

ing the complexity of legends, old and new.

In “Mind of Determination,” he recalls how

the laziest boy in the village entered a fish-

ing contest to win the marriage of the chief’s

daughter. With determina-

tion and the help of the gods,

he proves to be much more

than useless. The charac-

ters of this story are woven

together into a surrealistic

and symbolic wave. Try to

figure out the riddle before

you read the artist’s key. In

“Food Security,” Horipua

brings to the foreground one

of the greatest issues threat-

ening life in the Pacific –

climate change. With a keen

aesthetic balanced between

old and new, Horipua’s fables

I will ring true throughout the

blue continent.

How often does Guam

I have a renaissance-trained

artist turn his eye on her

history? Guam transplant

and Japanese painter, Yasu-

nori Sakakibara, returned

to Guam with his “Warrior

of Guam” finally complete.

“Warrior of Guam,” acrylic

by Yasumori Sakakibara

Both a love letter to Guam and a tapestry of

her history, this painting is worthy of a museum

and must be explored in person.

In a single sculpture, Rebecca Rae Davis

confronts the reality of Apra Harbor’s marine

life. “Bondage of Guam” depicts a small reef,

wrapped in a chain with a gift tag: Prop-

erty of U.S. Government. A minimalist artist,

with impact in every stroke, Davis reflects in

“Contact” the somewhat miraculous, almost

heavenly way history books depict the moment

the military entered Guam: like a golden anchor

descending from the sky. On

brown parchment paper,

with a package of colored

pencils Davis confronts the

reality others would rather

hide behind their palm trees.

It’s easy to fall in love with

an island for its tropical

beauty, and the museum has

no shortage of breathtaking

beach scenes. Lindsay Kane,

on the other hand, followed a

strange vision and drew her

own “Jungle” as if made from

hands. Instead of breadfruit,

palm leaves, and sword

grass, she drew fingers and

fists holding those shapes –

from far away you couldn’t

tell the difference.

Up closethe scene springs into a

strange and frightening

daydream. But hey, if you

thought the banana leaves

were that sensitive, wouldn’t

you watch your step?

SUNDAY, MAF

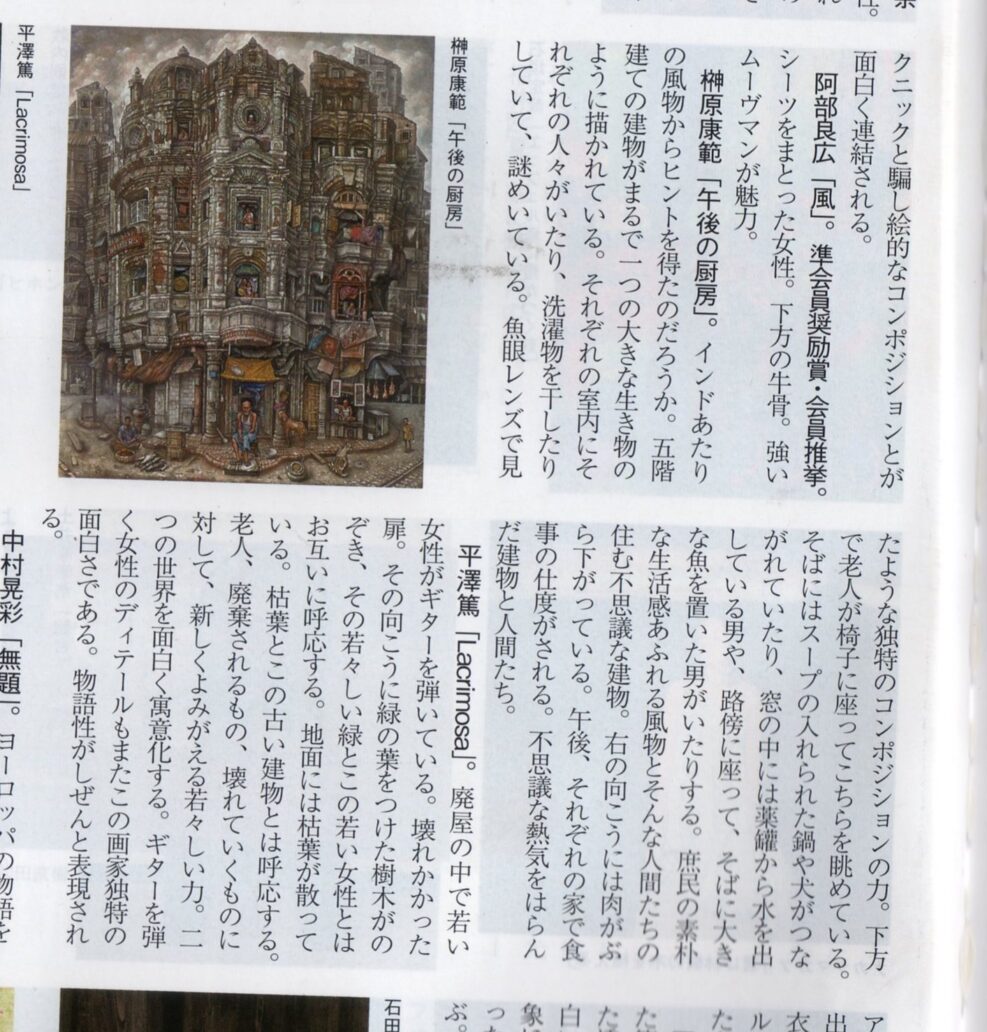

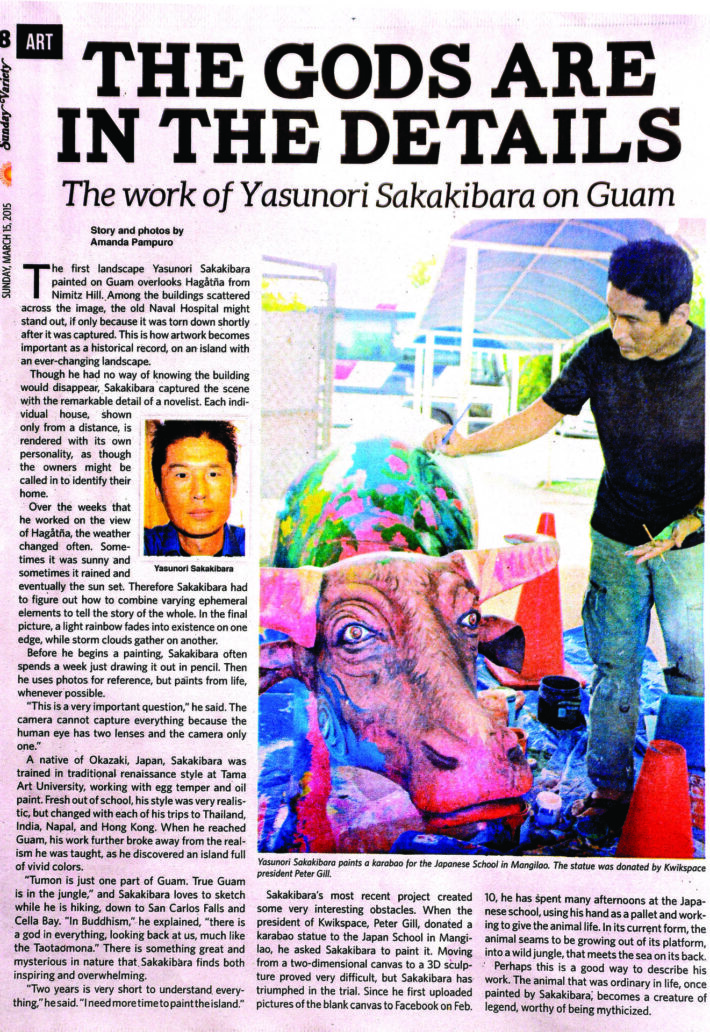

The first landscape Yasunori Sakakibara painted on Guam overlooks Hagåtña from Nimitz Hill. Among the buildings S scattered across the image, the old Naval Hospital might stand out, if only because it was torn down shortly

after it was captured. This is how artwork becomes

important as a historical record, on an island with

an ever-changing landscape.

Though he had no way of knowing the building

would disappear, Sakakibara captured the scene

with the remarkable detail of a novelist. Each indi-

vidual house, shown

only from a distance, is

rendered with its own.

personality, as though

the owners might be

called in to identify their

home.

Yasunori Sakakibara

Over the weeks that

he worked on the view

of Hagåtña, the weather

changed often. Some-

times it was sunny and

sometimes it rained and

eventually the sun set. Therefore Sakakibara had

to figure out how to combine varying ephemeral

elements to tell the story of the whole. In the final

picture, a light rainbow fades into existence on one

edge, while storm clouds gather on another.

Before he begins a painting, Sakakibara often

spends a week just drawing it out in pencil. Then

he uses photos for reference, but paints from life,

whenever possible.

“This is a very important question,” he said. The

camera cannot capture everything because the

human eye has two lenses and the camera only

one.”

A native of Okazaki, Japan, Sakakibara was

trained in traditional renaissance style at Tama

Art University, working with egg temper and oil

paint. Fresh out of school, his style was very realis-

tic, but changed with each of his trips to Thailand,

India, Napal, and Hong Kong. When he reached

Guam, his work further broke away from the real-

ism he was taught, as he discovered an island full Yasunori Sakakibara paints a karabao for the Japanese School in Mangilao. The statue was donated by Kwikspace

of vivid colors.

“Tumon is just one part of Guam. True Guam

is in the jungle,” and Sakakibara loves to sketch

while he is hiking, down to San Carlos Falls and

Cella Bay. “In Buddhism,” he explained, “there is

a god in everything, looking back at us, much like

the Taotaomona.” There is something great and

president Peter Gill.

Sakakibara’s most recent project created

some very interesting obstacles. When the

president of Kwikspace, Peter Gill, donated a

karabao statue to the Japan School in Mangi-

lao, he asked Sakakibara to paint it. Moving

10, he has spent many afternoons at the Japa-

nese school, using his hand as a pallet and work-

ing to give the animal life. In its current form, the

animal seams to be growing out of its platform,

into a wild jungle, that meets the sea on its hark